Like feet stuck in the mud

Rwanda: Decades after the genocide, the country is still trying to present itself as a nation, which is a pure façade. Many people are still trapped in the past.*

In April, life in Rwanda comes to a standstill. The inhabitants recall the genocide of the Tutsis and mourn this. Sports and music are prohibited. Swimming pools, bars, restaurants, and dance clubs are closed. There are radio and television broadcasts of commemorative events. The land is playing dead.

If 35-year-old Aminata Nsengimana weren’t a Rwandan, April would be her favorite month. Her 5-year-old son was born in April and her second child will also be born sometime this April. It’s a tragedy. “We won’t ever be able to celebrate his birthday because you can’t celebrate in Rwanda in April,” she says. “That month is reserved for the genocide.” The family celebrates its eldest son’s birthday in another month. “There aren’t many reasons to celebrate around here,” says Nsengimana. “We must not forget the few that there are. We owe this to our children.”

No psychologists

Twenty-three-year-old Charles Mugabe just finished secondary school – years too late. “After the genocide I couldn’t go to school,” he says, explaining his situation. “At the time, I worked to survive.” On April 11, 1994, together with his parents, his older brother and a pregnant aunt, 8-year-old Mugabe fled and sought shelter in Nyamata Church. This was only a few days after the massacre of the Tutsis began. His uncle and two sisters hid in the moor.

Mugabe hid under his brother’s corpse and pretended to be dead for two days before fleeing to the moorland.

“As an 8-year-old, you still believe that you will find something like mercy in the Lord’s house,” says Mugabe. He kept his faith in God, but not his belief in mercy. The Hutu militants stormed the church with machetes, arrows, bows, and nail-studded clubs and massacred some 7,000 people. Mugabe hid under his brother’s corpse and pretended to be dead for two days before fleeing to the moorland.

In the church, thousands of blood-soaked clothes still recall the massacre. (Photo: Wüthrich)

The mortal remains of the dead are stacked up in the church’s cellar. (Photo: Wüthrich)

Charles Mugabe has never undergone psychological treatment. There aren’t many psychologists in Rwanda. As a psychologist specializing in posttraumatic development disorders, Birgit Wagner spent a month teaching at the National University (NUR) in Butare in August 2008. “Most of the fifty psychology students at NUR were themselves traumatized,” says Birgit, who is a research assistant at the Institute for Psychopathology and Clinical Intervention in Zurich. “In the West, a care team takes care of people like this and treats them for many years. In Rwanda, they have to try and live with the trauma.” Psychologists, trauma experts and the appropriate institutions aren’t the only things lacking; basic knowledge is too. Most students don’t even have a book. There’s also a lack of educational material at the university level. The country itself isn’t even aware of the few articles and studies written about posttraumatic developmental disorders in Rwanda. The victims are left to cope with the trauma on their own.

“We have to keep living our lives”

The survivors, meanwhile, are once again confronted with the perpetrators from the past. Many of the people who were convicted returned to their villages after serving their sentences. Former enemies became neighbors. “Three men who were involved in the church massacre live near me,” says Charles Mugabe. When the Gacaca court summoned the perpetrators to answer for their actions, he testified against them.

Gacaca is a traditional legal system in which the village community acts as a judicial authority. During the trial, Charles Mugabe learned where the body of his uncle Patrice was buried. He then excavated the remains and placed the skull in one of the burial chambers under Nyamata Church. “I forgave the perpetrators,” he says soberly. “The dead do not come back. We have to keep living our lives.” He will, however, never again trust these people. Even now, the fear of getting murdered by them is great. When he comes upon the perpetrators in the dark, they do not greet him.

He said he didn’t do anything, didn’t see anything, didn’t hear anything. However, after the genocide and after the Tutsi rebels took over, he fled to neighboring Congo.

When Habimana A. (full name withheld by the author) appeared before the Gacaca court, it was the end for him. The 45-year-old was supposed to comment on what happened during the genocide. He said he didn’t do anything, didn’t see anything, didn’t hear anything. However, after the genocide and after the Tutsi rebels took over, he fled to neighboring Congo.

He only returned to Rwanda two years later. Because he refused to make a statement, he ended up spending six months behind bars last year – a mild punishment compared to the lifelong detention some genocide offenders received. As late as 1998, 22 of those convicted of genocide were executed. In Rwanda, the death penalty wasn’t abolished until mid-2007.

For Habimana, though, the six-month sentence was enough to destroy his life. “As a former prisoner, I will never again be able to get a job working for the state or the local community,” he explains. “I am ruined. I try to survive with odd jobs. But the past feels like my bare feet are stuck in the mud.” He doesn’t ask himself whether he’s guilty. Habimana sees himself as a victim. When he returned from the Congo, he was labeled a perpetrator and expropriated. “And what is a man without any land?” he asks. “A nobody – a person without a future. Without an opportunity to feed his family.”

Poverty and progress

There are thousands of men like Habimana in Rwanda. Land in the East African state has become scarce. Rwanda isn’t even two-thirds the size of Switzerland. With more than 10 million people, however, it has a much higher population density. Ninety percent of the working population works in agriculture. Some 100,000 young people enter the job market every year and less than one percent find employment. About 60 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. Many can’t even afford to pay for the basic and compulsory “mutual” health insurance, a fact confirmed by an employee of Rwanda’s healthcare system. The cost of this insurance is two francs per year.

“The land of a thousand hills”: green, fertile, but too small for the growing population. (Photo: Wüthrich)

Girl on her way to work in the fields. Most of the people are self-employed. (Photo: Wüthrich)

On the international stage, Rwanda tries to present itself as a booming economic market. It is trying to lure international investors from China, Dubai and the United States. A convention center and a new airport are in the planning stages. Its first casino recently opened. The large supermarket in the center of Kigali sells Western products. Wireless Internet works perfectly in the capital.

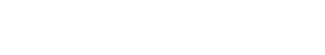

Custom-made suits and clothes

“Around here we don’t feel anything of this boom,” says 33-year-old André Bakengo, a Congolese who has worked as a tailor in Kigali for eight years. He’s in his studio six days a week, ideally for a daily wage of almost five francs. His workplace is located at the back of a clothing store, where foot-driven Singer sewing machines are the basic equipment. Three other Congolese tailors work here too. They are all refugees from North Kivu who are trying to build a new life in Rwanda. The customers are wealthy natives as well as Western employees from relief organizations and embassies. “Who else has money for custom-made suits and clothes in this country?” asks the father of five cynically. But for a few months now, it seems, these people also haven’t been ordering as many custom-made clothes as they used to.

Life in Rwanda is safe, but also expensive. The rent, food and schools for the kids make a dent in the family budget.

Bakengo’s wife and kids only recently moved to Kigali. The political situation in North Kivu became too dangerous. Life in Rwanda is safe, but also expensive. The rent, food and schools for the kids make a dent in the family budget. School is officially free in Rwanda. In reality, however, the parents have to pay for books and uniforms. “Not to mention the monthly motivational awards for the teachers and the fee for the custodians and cleaning staff,” adds Bakengo. If you don’t pay, you can’t go to school.

André Bakengo at work: six days a week, ideally for a daily wage of five francs. (Photo: Wüthrich)

Schools without books

Rwandan schools are short on books for the approximately 2.5 million students. In classes with up to 80 children, four to five students often share a book. The books are out of date and, since a few months ago, have also been printed in the wrong language. At the end of 2008, English replaced French as the language of instruction, though Kinyarwanda, the national language, continues to be used as well. This is the Rwandan government’s way of stressing the country’s distance from the former colonial powers of Belgium and France.

Another reason for English-language instruction is to call attention to Rwanda’s closeness to the neighboring English-speaking countries of Burundi and Kenya. The only thing that isn’t clear is how to implement the language change. Like many of his professional colleagues, Théoneste Habyarimana is one of the country’s 50,000 teachers who hardly speaks a word of English. “We must respect the government’s decision,” he says, emphatically. “The change is a step towards the future.” But he also doesn’t quite know how to implement this step – it certainly won’t happen very soon.

Post-genocide Rwanda

During the 1994 genocide, 800,000 people died. Radical Hutus didn’t just murder Tutsis, but moderate Hutus too. As a result of the genocide, about 2.5 million inhabitants fled, and 130,000 suspected perpetrators, mainly men, were imprisoned.

Today, Rwanda is the world’s first country with more women than men in parliament. The women comprise 55 percent. The preponderance of women is not only due to the fact that the country promotes women’s participation in government, but, above all, to the genocide. Women were forced to assume leadership roles and administrative functions.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame is an authoritarian leader. Political opposition and freedom of the press hardly do exist. The organization, Reporters Without Borders, listed Kagame as one of the world’s greatest enemies to press freedom. The country is dependent on development aid. The international community pays for about 50 percent of Rwanda’s total budget. In the future, this is supposed to change radically. The “Vision 2020” development strategy aims to transform the country into an important East African investment platform. Rwanda’s political stability could be challenged by the conflicts in neighboring countries and by internal tension.

https://elkverlag.ch/genozid-voelkermord-am-beispiel-ruanda.html

* The author worked in Rwanda’s prisons in 2007/08 and did so as a delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). After her resignation, she returned to Rwanda as a journalist and conducted several weeks of research there. Published in the “Wochenzeitung” (WOZ) in April 2009, this article was nominated for the FBZ Media Prize for Independent Journalism in 2010. The author wrote several newspaper articles on Rwanda and genocide. She also lectured in schools and is the author of teaching materials about Rwanda that were published by elk Verlag.