Bilingualism fights poverty

In Thailand’s schools, the curricula and course content often exclude ethnic minorities from participating in the classroom. However, a Swiss funded project shows that things can also take a different course.

Anong had been looking forward to her first day of school for months. But her school experience becomes a disaster. She doesn’t understand the teacher’s language. In the coming months, her tremendous disappointment is compounded with frustration, boredom and ultimately a lack of interest in the material taught. Anong leaves school after a few years. She has no job perspectives and expects her first child at 16.

The fact that they do not understand the language the teachers speak at school has nothing to do with a lack of intelligence, but with their background. Thai, the official national language, is not spoken in the mountain villages.

Anong’s case is emblematic of the lives of children and adolescents who grow up in remote mountain villages in Thailand. The fact that they do not understand the language the teachers speak at school has nothing to do with a lack of intelligence, but with their background. Thai, the official national language, is not spoken in the mountain villages. The people communicate in the various tribes’ respective languages that include Pwo Karen, Mon and Hmong. Thai is a foreign language for these ethnic minorities who mainly live in the areas bordering Laos and Myanmar. They hear Thai for the first time at school, where the teachers don’t speak the local languages. After completing their studies, the centrally managed Ministry of Education sends these teachers all over the country, where they teach in the nation’s official language, which is also the school’s official language, using books provided by the state.

This “mutual lack of linguistic understanding” has fatal consequences for kids and adolescents. Compared with the national average, the children in the mountain villages do worse at school. They leave school earlier. They rarely complete high school or attend university. However, it’s hard to find work without an education. The young people remain stuck in the same downward spiral of poverty as their parents – stigmatized by their background and language.

Learning your native language

“If the native language is not supported and fostered, this not only affects the students’ school achievements and later their professional choice, but also their sense of self-confidence and the way they see themselves,” says Brigit Burkard, program coordinator for South East Asia at the Pestalozzi Children’s Foundation. “Aspects of their own identity, their own history and their own strengths atrophy. Knowledge, history and cultural diversity are lost.” Located in Appenzell and financed by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation as well as by private donations, the foundation has funded a project to promote bilingual education for ethnic minorities since 2007.

The strategy is clear: The classes at school should be held in the pupils’ mother tongue, because students taught in their native language will learn a new language more easily. Thai is taught as a second language. There is an instructor in the classroom who speaks both languages or there is a team consisting of a Thai instructor and an assistant who translates the course content into the local language. The project finances the training of teachers and assistants, the development of teaching materials and curricula, as well as further educational training for the population. Serving a total of 2,000 children from ethnic minorities, six schools benefit from the bilingual education. Moreover, some 100 teachers are trained to teach bilingually. The annual costs amount to roughly €143,000. It is a nine-year project that runs until the end of 2015.

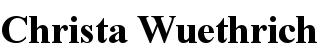

Learning their native language: kids in a remote mountain school. (Photo: Wüthrich)

“I don’t know of any comparable project in Thailand or in the whole region that introduces the mother tongue in such a professional manner,” says Burkard, adding: “In other words, in a professionally linguistic manner: On the one hand, by working with the villagers to incorporate their cultural background; on the other, by maintaining a dialog with the Ministry of Education so we can tie our teaching to the system, since our work is not just limited to schools.”

Saving traditional Knowledge and Vocabulary

On-site partner organizations play a decisive role. Panne Bharistha Sreshthaputra, project coordinator at the Foundation for Applied Linguistics (FAL), plays a key role in this. The 40-year-old visits the schools in the mountain villages – for example, in Baan Pui, which is about four hours by car north of the city of Chiang Mai. Between rice fields and bamboo forests, about 300 families live in simple wooden huts. The first school was built 15 years ago. Electricity is a fairly recent development as is the presence of a TV in almost every house. Pwo Karen is the language spoken. It has its own characters and hardly shares any similarities with the official Thai language.

Hardly anyone is proud of the Pwo Karen language. “If you want success, a good job and money, then you speak Thai,” says one of the village elders. “Just watch some TV.”

Hardly anyone is proud of the Pwo Karen language. “If you want success, a good job and money, then you speak Thai,” says one of the village elders. “Just watch some TV.” To make the people in Baan Pui aware of the school project, workshops are held in the village church. “Without the support of the entire population, a school project like this can’t be implemented,” says the local project coordinator, emphatically. “The vocabulary of the Pwo Karen language lives in the minds and hearts of the people here in the village.”

Hardly anyone is proud of the Pwo Karen language. Village elders. (Photos: Wüthrich)

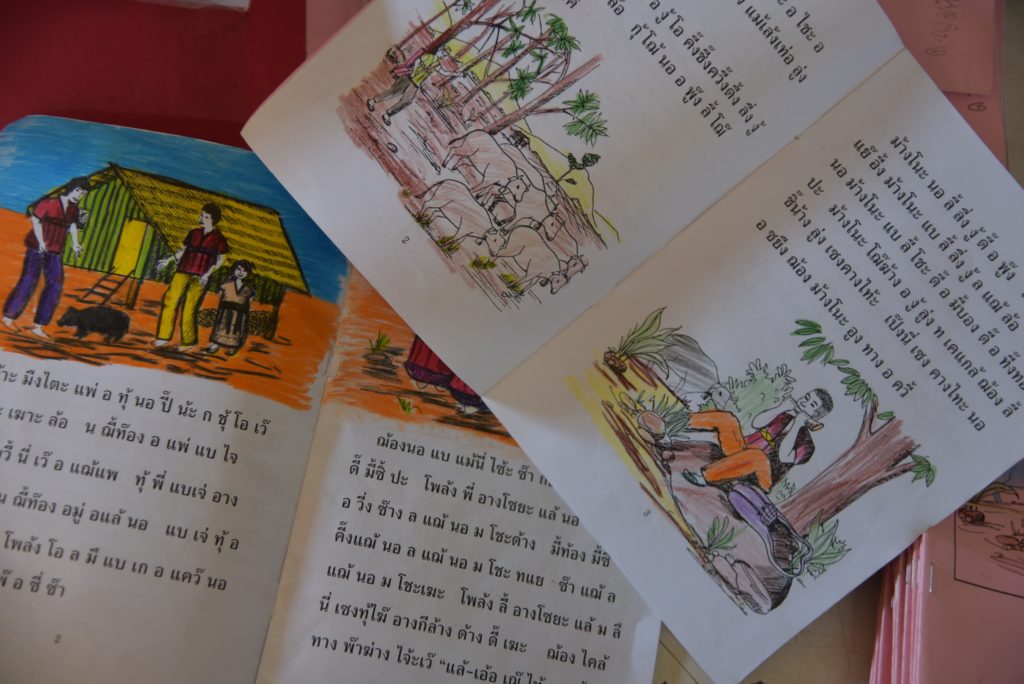

Apart from the Bible, there wasn’t a single book written in Pwo Karen. With the start of the project seven years ago, this has changed: The first dictionary is planned for this year. The Pwo Karen schoolbook series has been steadily expanded over the past few years. Today there are 18 books and they were developed together with the villagers. They are about village life and community traditions – knowledge that would otherwise get lost. In a few decades, perhaps no one will remember how to make traditional bamboo instruments; how to cook a fine mountain frog soup or fry bamboo worms; or even how to make a roof for a house or irrigate the rice fields in a traditional way. And who would know that “Ang-Tu,” the Pwo Karen word for marriage, literally means “Eat the pig”?

The Pwo Karen schoolbook series has been steadily expanded over the past few years. (Photo: Wüthrich)

No budget, no future?

Among teachers, parents and the Ministry of Education, the project only meets with favor. Compared to the national level, the students’ performance has improved. Hardly any kids leave school before the obligatory school period comes to an end and increasingly more young people are able to make the leap to secondary schools or even universities. The kids are proud of their language and background. Project coordinator Sreshthaputra hopes that some of the students will choose the teaching profession and will then return to their villages to teach. The school project appears to have won the first round in the fight against the downward spiral of poverty. The future nevertheless doesn’t look rosy.

“While there is a law that allows teachers to teach ethnic minorities in their native language, there is no budget to implement such teaching and no teacher training exists for it.”

At the end of this year, the project is officially over and funding from Switzerland becomes a thing of the past – that is, unless the Swiss foundation decides to extend the funding*. Although it is regarded as a flagship program for the whole region, there are no alternative donors in sight – in other words, no Thai sponsors or international foundations are in sight to take over the financing. School Director Piyapat Mee-nam, who has directed the school in Baan Pui for six years, is worried about the future of this school which has about 230 children. “It is indeed clear to the Ministry of Education how effective bilingual education is,” says Mee-nam. “Ministry employees visited our school as part of the program, but the money for this will be missing in the future. While there is a law that allows teachers to teach ethnic minorities in their native language, there is no budget to implement such teaching and no teacher training exists for it.”

*In 2016 the Swiss Foundation secured an additional financial support until May 2017.

Published in March 2015 in Südwind Magazin.